The almost complete eradication of the native buffaloes ignited an environmental catastrophe that devastated the continent for a decade.

Sy Montgomery's most recent book, The Magnificent Migration is an enjoyable, leisurely read that effortlessly transports the reader into the midst of perhaps the largest mammal migration in the world.

This migration takes place in the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, part of the larger Serengeti/Masai Mara ecosystem that includes Ngorongoro Crater, a vast volcanic sinkhole and World Heritage Site that serves as an entry point to the Serengeti.

The book is written up from journal entries, and chronicles a luxury safari with all its trials and tribulations. It reflects on the author's youthful infatuation of Africa’s wildlife, travelling through the Serengeti with six of Montgomery’s close friends and their dedicated guide. The group included two New York Times best-selling authors, one Chicago-based evolutionary scientist, a computer expert and his tight rope-walking son.

Search

The group travelled through Serengeti National Park spending nights at a series of safari lodges. They were in search for migrating herds of wildebeests, hoping to observe their elaborate mating rituals, and in the company of Dr. Richard Despard Estes, the world’s foremost expert on these odd-looking antelopes and pioneer of antelope behavior (ungulate ethology).

Just imagine the sight of over one million wildebeests in separate herds of tens of thousands-all on the move at once and, en route, collecting an estimated 200,000 Zebras, 500,000 Thompson’s and Grants Gazelles, 97,000 Topi and 18,000 Eland.

As if that weren’t enough, hard on the heels of these herds as they passed through diverse wildlife habitats are thousands of various predators and scavengers: lions, leopards, crocodiles, hyenas, jackals, and vultures.

The almost complete eradication of the native buffaloes ignited an environmental catastrophe that devastated the continent for a decade.

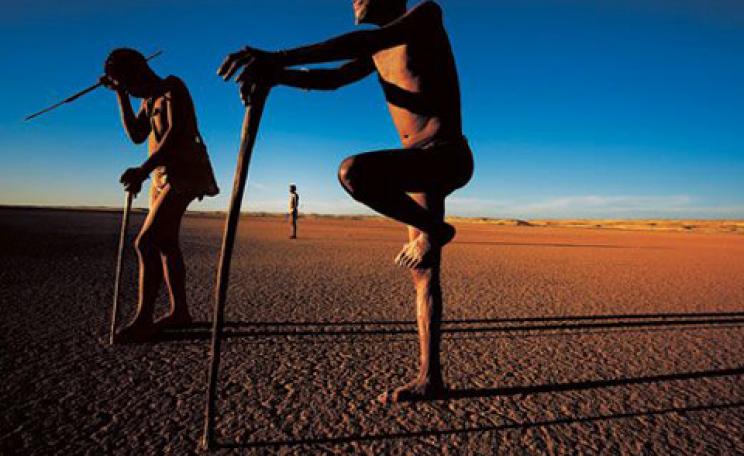

Sy Montgomery recalls: "I dreamed of visiting deserts and jungles and of course the storied Serengeti. Before I could even read, I enjoyed looking at the photos of National Geographic magazine, showing all sorts of fascinating African animals and beautiful people with rich cultures.

"I especially remember the pictures of young, ponytailed Jane Goodall consorting with chimps who were her friends. Even as a child, I thought that was as it should be: animals and people together, sharing the world.”

Territory

The wildebeest (Connochaetes) is the most abundant species of antelope in all Africa (the continent has an estimated seventy-five different antelope species). There are two separate species and five distinct subspecies, of wildebeest, all of them in Africa (the fossil record suggest these two species diverged about one million years ago, resulting in a northern and a southern species). They are all called gnu’s. Of them all, only the Western White-bearded wildebeest still thrives in immense migratory herds.

During the mating season, the migratory mature bulls hold small territories that they advertise and defend until the females stream out of the area. In a nutshell, the female wildebeests are seeking food, water and shade while the males seek to mate.

We learn from Montgomery that the Serengeti itself was sculpted by the gnu’s endless circular trek. Its grasses are cropped by their teeth, enriched by their manure, churned by their hooves. During the mating season, aggressive males bash small bushes and saplings with their horns, using them like punching bags.

Research by Richard Despard Estes and others has shown that this also keeps the savanna open, preventing bush from encroaching. Even a component in the gnu’s saliva has been found to nourish the grass they graze (a similar natural chemical has been found in the saliva of North American bison).

The book also helps to dispel some of our widely held beliefs of the Serengeti migration. For example, our perception of migrating wildebeest, largely based on a healthy overdose of National Geographic TV, is of stampeding herds in a mass panic, trying desperately to escape the awaiting jaws of lions and crocodiles. But this far from the truth. According to Montgomery, it’s a much more leisurely affair (“One reason they’re running on TV: the filmmakers in helicopters overhead frighten them”).

Behaviour

But where do the other estimated twenty-eight species of wild fauna, who depend on the migration, fit into the scheme of herds of wildebeests on the move?

Zebras, for example, chomp the taller grasses and reveal the understory for the wildebeests; the wildebeests pay the favor forward. They crop the medium-length grasses to uncover even shorter plants, the food of the Thompson's and Grant's gazelles.

Montgomery has been criticized as being too anthromorphic, attributing human motivation, characteristics, or behavior to animals, for example (something already known to Indigenous Peoples as well as wildlife biologists).

But in the last generation an entire field of cognitive ethology, the study of animal behavior that deals with the influence of conscious awareness and intention on the behavior of an animal has sprung up around the observations of scientists and naturalists.

To this we owe a debt of thanks to the late American zoologist Donald Redfield Griffin who, forty years ago, established the foundations for researches in the cognitive awareness of animals within their habitats. Montgomery has simply continued to expand in that pioneering tradition.

Epic

Montgomery tells us that animal journeys have been taking place since at least the Jurassic period, starting over two hundred million years ago. From the elements in teeth shed by dinosaurs 150 million years ago, scientists know that the giant plant-eating sauropods of North America, made regular seasonal journeys from low to high ground to escape drought and animal food shortage.

The book’s focus is not only on the wildebeest and their epic migration. In side boxes, the book also mentions other wildlife migration wonders - such as the epic migration of the Monarch Butterflies, flying one billion strong on a 900 hours flight from their birth sites in the USA and Canada to Mexico and Southern California, and shimmering shoals of migrating Pilchard Sardines traveling from their spawning site in the Agulhas Bank, a broad, shallow part of the southern African continental shelf, to the east coast of South Africa.

Sadly, Montgomery does not include the other epic antelope migration that takes place in the Republic of South Sudan and involves 1.2 million White-eared kob and tens of thousands of Topi and Mongalla gazelles through Boma National Park.

Montgomery explained: “Alas, we only had time and money to visit Tanzania while researching the book. The kob migration is fantastic, and I would love, love, love, to see it! When mentioning other migrations in the book I was looking for variety, so concentrated on presenting animals vastly different from the wildebeest or creatures on continents other than Africa.”

Pressure

One of the most poignant stories of the book is that of the bison or the American Buffalo. A sad but instructive tale. Their tale has relevance not only for the existing herds of wildebeests, but for all the world's prolific wild species facing the pressures of humanity's considerable footprint.

Two centuries ago, the prairie ecosystem in mid-America resembled the African savanna. So for most of the nineteenth century, the American plains of the mid-west the vast herds of bison that grazed the prairies with their calves (two centuries ago, the prairie ecosystem in mid-America was remarkably like the African savanna).

In fact, there were anywhere from 30 million to 75 million bison roaming the American plains. But by mid-century, an estimated 300,000 bison were being slaughtered for their hides and tongues (considered a delicacy) by white trappers who had invaded the prairies.

Astonishingly, by 1884, only 325 bison are said to have remained in the wild- twenty-five of them in Yellowstone National Park.

Montgomery said: “The almost complete eradication of the native buffaloes ignited an environmental catastrophe that devastated the continent for a decade."

Conservation

The book also contains some very serious underlying conservation themes of climate change, urbanization, modernity in the form of new roads, the potential downside of eco-tourism developing Africa.

Even on Tanzania’s wildlife reserves and national parks where wild species are protected by law, poachers are having a field day killing gnus and other antelope species for food. In most cases, this is done with the ubiquitous poacher’s snare.

If the conservationists have gone high tech with their camera traps and telemetry tracking collars, which track wildlife using satellite technology, then the poachers have gone low tech with menacing snares made of a length of wire tied in a slip knot and attached to a heavy rock or tree.

The Serengeti De-Snaring Program, organized by the Frankfurt Zoological Society and funded by Serengeti Park hotel owners and tour operators, has removed almost 30,000 snares and freed 286 live animals. In 2018 alone, over 17,000 snares were collected in the Serengeti (it’s estimated that one hundred thousand wildebeests are poached annually).

While this is only one-third of the American bison slaughtered annually during the mid-19th century, Africa’s urban areas, where the bushmeat demand has increased, area growing at around 5% annually and it’s only a matter of time until that figure will surely increase.

This handsomely illustrated coffee-table book is 11 inches by 9 inches and contains a variety of contemporary colored and vintage black and white photographs. The majority of the colored images are by fellow travelers Roger and Logan wood-old friends of both Montgomery and Estes. It’s quite suitable for young readers on upwards.

This Author

Curtis Abraham is a freelance writer and researcher on African development, science, the environment, biomedical/health and African social/cultural history. He has lived and worked in sub-Saharan Africa for over two decades with his work appearing in numerous publications including New Scientist, BBC Wildlife Magazine, New African and Africa Geographic.