Even in remote places such as Irkutsk in Siberia with its very short growing season, I have seen people cultivate an great variety of vegetables, including cucumbers and tomatoes, in well insulated greenhouses, both for home supply as well as for sale in

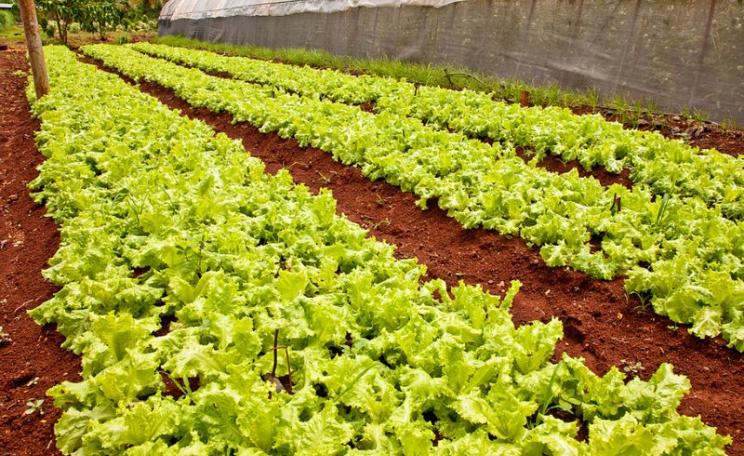

We need to find efficient and environmentally enhancing ways of feeding ourselves. To this end we need to initiate new processes of 'ecological densification' - making good, well considered use of limited areas of land - to meet increased food demands by increasing numbers of people.

In many countries large minorities of people grow food in and around cities. In countries where rural-urban migration is prevalent, many people become urban and peri-urban food producers, on a full or part-time basis.

According to the UNDP, some 800 million people were engaged in urban agriculture worldwide in 1999. Of these, 200 million were thought to be market producers, with 150 million people employed full time.

Cities such as Havana, Accra, Dar-es-Salaam and Shanghai have been studied extensively. But in thousands of other cities people are also quietly getting on with producing food.

Urban agriculture in developing countries can greatly contribute to urban food security, improved nutrition, poverty alleviation and local economic development. In developed countries it can contribute to the reduction of 'food miles' - with local distribution via farmers' markets and specialised shops.

Putting organic wastes to productive use

In recent years I had the opportunity to witness urban agriculture in many places. I was interested in this because, among other things, urban agriculture can help cities to put organic waste materials to good, productive use.

In order to survive in a globalising food system, urban farmers must be highly innovative and adaptable. They grow fruits, vegetables, herbs, tree seedlings and ornamental plants, as well as raising animals. They have to cope with city constraints and tap as effectively as possible into urban assets and resource flows.

Whilst often discouraged by local authorities until recently, urban food production is being practised in many places. In recent years its importance has been increasingly acknowledged by researchers, politicians and urban planners for its potential of creating viable livelihoods for urban people.

Urban agriculture often builds on ancient traditions. Historically, most cities 'emerged' out of their own productive hinterland, and some contemporary cities are still deeply 'embedded' in their local landscapes, even in Europe.

Many Mediterranean cities are still surrounded by orange and olive groves, vineyards and wheat fields on which a large proportion of their food requirements are grown. They still have very strong relationships to their immediate hinterland.

China's urban farming traditions live on

I found the same in China, which has an age-old tradition of settlements permeated with food-growing areas. Today, at a time of very rapid urban-industrial growth, urban agriculture is still a very important issue for the Chinese.

Even megacities such as Shanghai, with about 15% population growth per year, one of the fastest growing cities on the planet, maintains its urban farming as an important part of its economic system.

Even in remote places such as Irkutsk in Siberia with its very short growing season, I have seen people cultivate an great variety of vegetables, including cucumbers and tomatoes, in well insulated greenhouses, both for home supply as well as for sale in

A major shift has taken place, however, from 'intra-urban' to 'peri-urban' agriculture. As housing and office developments grew within the city, farmland there has been lost and food growing has shifted increasingly to the city's periphery.

Tens of thousands of hectares on the outskirts of Shanghai are intensely cultivated with a great variety of vegetables. The Chinese like to cook fresh, locally grown vegetables. Stir-frying wilted vegetables is not regarded favourably. Glass and polythene greenhouses are now much in evidence, producing three to four successive crops a year in Shanghai's warm climate.

On the outskirts of Beijing, too, vegetable cultivation is much in evidence. But farmers have had to develop ingenious systems to cope with the much colder climate there and with limited water supplies. Greenhouses, too, are much in evidence.

During frosty conditions in January and February, they cover their polythene tunnels with several layers of bamboo mats in the evening to keep the heat in at night. Few growers in and around Beijing use coal fired heating systems in their greenhouses to cope with the icy conditions outside.

Closing the nutrient loop

In Chinese cities, 'closed-loop' systems, using night soil as fertilisers for urban vegetable growing, are still practised in some places. The night soil is diluted, perhaps ten to one, and then ladled onto vegetables beds.

I was told that people prefer vegetables grown with night soil fertiliser because of their superior taste. But most new apartment and office buildings, which are in evidence everywhere, have water closets, and it remains to be seen whether appropriate ways of using their waste water in urban farming can be developed.

In Russia, too, peri-urban food growing is an age-old tradition, with many people retreating to their dachas at weekends to cultivate crops in highly productive gardens. In St. Petersburg many people are involved in peri-urban farming: there are some 560,000 plots being cultivated on the periphery of the city.

Even in remote places such as Irkutsk in Siberia with its very short growing season, I have seen people cultivate an great variety of vegetables, including cucumbers and tomatoes, in well insulated greenhouses, both for home supply as well as for sale in markets.

In South Africa, of course, during the apartheid days it was forbidden for the black majority to grow food on land within and around cities, because that meant people were there to stay. But in today's South Africa a dramatic growth of urban agriculture is under way as people get a permanent foothold in their towns and cities.

And throughout Africa, in Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania and elsewhere, much food growing takes places within cities, because they are often still very low density and there is room for food growing. Women tend to be the cultivators in urban areas.

At the heart of urban sustainability

Urban agriculture is an important aspect of the wider issue of urban sustainability, by being able to supply food from close-by as well as offering livelihoods for city people.

Another important issue, as already discussed, is the efficient use of nutrients from the urban metabolism that would otherwise end up as pollutants in rivers and coastal waters.

In many cities attempts are being made to use waste water in urban food production. This applies particularly to cities in hot and dry places. For instance, in Adelaide, Australia, tens of thousands of hectares of land on the edge of the city are cultivated using waste water from the city for irrigation, growing vegetables as well as grapes and fruit.

There is some concern about trace quantities of heavy metals that could accumulate in the soil, but it would take decades to cause any problems. Establishing new waste-water crop irrigation system, as Adelaide has done, is crucial for regenerative systems of urban agriculture.

This article is an extract from Creating Regenerative Cities by Herbert Girardet, published by Routledge (Abingdon and New York) 2014.

Professor Herbert Girardet is a cultural ecologist, working as and international consultant and author. He is a member of the Club of Rome and an honorary member of the World Future Council. He is a former chairman of the Schumacher Society, UK. He is a UN Global 500 Award recipient, an honorary fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects. He has developed sustainability strategies for London and Bristol and, as 'Thinker in Residence', for Adelaide, South Australia. His 13 books include EARTHRISE (1992), THE GAIA ATLAS OF CITIES (1992 and 1996); CITIES, PEOPLE, PLANET - Urban Development and Climate Change (2004 and 2008); A RENEWABLE WORLD - Energy, Ecology, Equality (2009), and CREATING REGENERATIVE CITIES (2014).