We see our role as chroniclers of a global movement for environmental justice leading to social transformation in process, of a history of struggle that is actively creating new worlds and new possibilities

The environmental movement is for the ‘post-industrial’ age what the workers’ movement was for the industrial period.

Yet while strike statistics have been collected for many countries since the late nineteenth century no administrative body tracks the occurrence and frequency of mobilizations or protests related to environmental issues at the global scale, in the way that the International Labour Organization tracks the occurrence of strike action.

Over the past 5 years, a global team of researchers and activists, coordinated by the undersigned, filled this gap by creating the largest existing inventory on ecological struggles from around the world: The Global Atlas of Environmental Justice or EJAtlas. It includes both qualitative and quantitative data on thousands of conflictive projects as well as on the social response.

Environmental conflicts as potent forces for sustainability

In a Special Feature for Sustainability Science, the lenses of political ecology and ecological economics are applied to unpack ‘ecological distribution conflicts’ in 13 articles that explore the why, what, how and who.

Ecological distribution conflicts arise precisely when communities refuse to be polluted, to be contaminated, displaced and erased and decide to mobilize and rise up in social opposition.

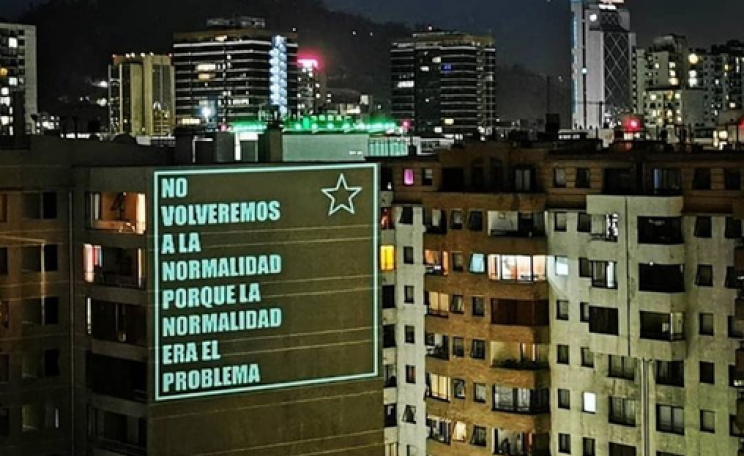

We underline the need for a politicization of socio-environmental debates, whereby political refers to the struggle over the kinds of worlds the people want to create and the types of ecologies they want to live in.

We put the focus on who gains and who loses in ecological processes arguing that these issues need to be at the center of sustainability science. Secondly, we demonstrate how environmental justice groups and movements coming out of those conflicts play a fundamental role in redefining and promoting sustainability.

We contend that protests are not disruptions to smooth governance that need to be managed and resolved, but that they express grievances as well as aspirations and demands and in this way may serve as potent forces that can lead to the transformation towards sustainability of our economies, societies and ecologies.

Debunking the fake solutions

While there exists broad consensus about the existence of the sustainability crisis, scholars mostly debate only market-based solutions, technological innovations and top-down policies.

We see our role as chroniclers of a global movement for environmental justice leading to social transformation in process, of a history of struggle that is actively creating new worlds and new possibilities

Yet the mainstream techno-managerial solutions proposed tend to overlook relations of power and issues of distribution, and to dismiss or minimize the import of political dissent.

Sustainability discourses often remain stuck in what is called a post-political space: a political formation that forecloses the political, the legitimacy of dissenting voices and positions.

At the same time communities around the world are organizing and coming out to the streets en masse to oppose or problematize the imposition of “development” projects, landfills, mines and even large renewable projects and climate fixes. In many places, they put their lives on the line to do so.

Guide to the Special Feature

The included articles touch on a range of countries and regions and themes:

- Overview and conceptual framework

- Transversal articles: worldwide conflicts related to wind energy and hydropower

- Regions: Andean countries, Central America, ex-Yugoslavia

- Countries: Venezuela, Sri Lanka and Brazil

- Single issues in one country: cement kilns in Spain and waste incineration in China

- Resistance-centered perspective on transformation

A couple of take home messages

Indigenous populations constitute 5% of the global population and 15% of the extremely poor and yet, they are affected in no less than 40% of the cases documented in the atlas.

Further, as Del Bene et al. and Navas et al. demonstrate, the cases where they do figure tend to include greater repression, criminalization and deaths

Beyond the violence, there are also stories that inspire. Numerous cases of projects on hold, stopped or redesigned. Twenty per cent of the projects documented have been stopped altogether.

This hints to the successes and also the difficulties of the environmental justice movements in contributing to improve the sustainability of the economy.

The EJAtlas may be considered a contemporary environmental history from below. As founder-directors and contributors of the project we see our role as chroniclers of a global movement for environmental justice leading to social transformation in process, of a history of struggle that is actively creating new worlds and new possibilities.

These Authors

Leah Temper, Federico Demaria, Arnim Scheidel, Daniela Del Bene, Joan Martinez-Alier work with the Environmental Justice Atlas. The full overview article is available online.