Deep Adaptation's anticipation of societal collapse - and the many possible configurations that it might take - is leading activists to take action in ways that they might not have done previously.

We've been here before. About ten years ago, when the Transition Towns movement began to grow enough to get noticed beyond its participants.

Suddenly criticism was directed at people who had been busy helping each other grow food, reduce emissions, and support each other with their grief about how badly our industrial growth society was destroying the basis for life. We were called "doomers" and “hair shirted environmentalists" who were "giving up" and the reason why more corporate-friendly environmentalists were not achieving much.

Read "Is Deep Adaptation flawed science?"

It can be convenient to blame others when one’s own cultural stories are crumbling. So in the Transition Movement, we responded to these criticisms by asking three questions: firstly, "what is working well and what isn’t?"; secondly, "what could our locale look like if we were the best we could become?", and thirdly, "what can we do right now to make that positive vision a reality?"

In asking these questions we promoted a different vision of the future and of what optimism might look like if we anticipate an end to a society based on unending industrial growth.

Action

The Deep Adaptation phenomena gained ground just then, in 2018. When the original paper came out and went viral, many people in the Transition movement connected with its message. The work of Professor Bendell since that paper came out has resonated with the movement, as he engaged in ideas from psychology, localisation, decolonisation and spirituality.

Interest in Deep Adaptation as a response to climate-induced societal collapse has grown to a point where some people want to make the idea go away. The favoured method is to repeat some of the claims that we heard before about Transition, that it is too gloomy and counter-productive and that such negative messages are disempowering.

Deep Adaptation's anticipation of societal collapse - and the many possible configurations that it might take - is leading activists to take action in ways that they might not have done previously.

Critics also attack the original paper from two years ago for being ‘faulty science.’ Looking at the criticisms, on balance, I believe they are weak and unhelpful to the environmental movement. Therefore, to inform the debate, I will summarise why Deep Adaptation is not faulty science at all, but a very necessary contribution to the field of environmental thought and action.

First and foremost, Deep Adaptation is robust and motivating science because it is not a single research paper but a new movement of both scholars and activists from around the world. Our anticipation of societal collapse - and the many possible configurations that it might take - is leading us to take action in ways that we might not have done previously.

People who believe that climate-induced societal collapse is possible, likely, inevitable or already occurring, now have a means of engaging and supporting each other to explore what this means for their own life, work, community and politics. Surely this is an important conversation to have at this time?

Complexity

Those who want to rid the world of this conversation resort to picking apart the original paper itself.

This paper is an important contribution to a growing field of credible scholarship on the real risks of societal collapse from the direct and indirect impacts of climate change and ecological degradation. Rather than critiquing specific problems with this academic paper, we can look at its merits, and how it contributes to the progress of knowledge.

There are six aspects to the original paper which are hallmarks of a necessary approach to research in a time of crisis, and that I encourage more scholars to embrace from now on.

First, in researching the paper, Professor Bendell sought to answer questions of urgent importance by drawing upon multiple fields of knowledge in a transdisciplinary way. At each step of analysis he sought to identify what is most relevant to our the desired outcomes - that is, flourishing human life and indeed all of life.

Bendell combined analysis of existing published theory and models with evidence from recent observational data, on matters such as sea levels and methane concentrations. This approach contrasts with the mainstream, in which the questions asked arise from the preoccupations of a particular academic discipline and therefore the conclusions are often so narrow as to not help us understand our world in all its complexity.

Nuance

That criticism of mainstream science is well established now in a field called "post normal science", which makes it clear that when humanity is facing emergencies - such as a pandemic or climate crisis - then traditional approaches to scientific research and analysis are inadequate.

This echos developments in what might be called post normal education. Taking a transdisciplinary approach as Professor Bendell did is challenging. You need to be able to assess what is the significant signal within the noise of a discipline and disregard points that are of no consequence beyond debates internal to a discipline.

There is often a lack of space for nuance, owing to the breadth of disciplines engaged in looking at climate and society. But it a person wishes to criticise from the standpoints of one of the disciplines, they will find a way to do so.

Bendell was clear about his own intentions, assumptions and emotions in relation to the topic. This is a departure from the pretence of objectivity, a position that is not achievable and hides the assumptions, frameworks and intentions that shape any inquiry or attempt to communicate knowledge.

Bendell also had no institutional, commercial or career interest shaping his agenda, analysis or findings. We know that academics need to both publish and promote their field to funders and regulators. But Bendell prioritised sticking with his conclusion and communicating that to his professional community over and above his career interest in having another journal article published.

Interests

This point is important to note, because we have seen decades in which fossil fuel companies have held influence over climate knowledge and policy. After decades of subverting the environmental movement, we can't suffer any more years of being reshaped and delayed by the clever tactics of vested interests.

For example, the nuclear industry relies on very long term investments and thus has an interest that neither policymakers nor investors anticipate disruptions to normal society in the coming decades.

There is a huge vested interested in ignoring the potential for collapse. Therefore, if any scientist offers their opinion on the future impacts of climate change on society, they should reveal any alliance with relevant vested interests, whether fossil fuels, the nuclear sector or others.

In addition, Bendell wrote the paper in a way that could gain emotional resonance with the reader. Why do we do any science if not to communicate what we find? Why write up science on a matter of global importance if not seeking to communicate widely?

Bendell used the increasingly popular academic method of auto-ethnographic writing to convey some of his own emotions. One can only imagine what would happen if more scholars did that.

Science

The Deep Adaptation paper broke new ground, in the English speaking world, in ways that have subsequently been supported by more recent findings.

Bendell's paper was published before the IPCC 1.5 degree report that dramatically changed global discussion by indicating that drastic cuts are needed year on year for a decade to have a chance of avoiding dangerous levels of warming. He reported on unpublished data on nonlinear sea level rise before the UN's World Meteorological Organisation confirmed it. The paper helped refresh the important field of the anticipation and preparation for societal collapse.

The sixth reason it is good science is that it is open to contestation, debate and revision, as the recent flurry of articles illustrates. Previous criticism led him to issue some corrections in February 2020 due to comments and critiques by eminent climate scientists Gavin Schmidt (Director, NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, USA) and Dr. Wolfgang Knorr (Lund University, Sweden).

Bendell has released an updated version on its second anniversary. Deep Adaptation is not just a paper, but a living body of research and social enquiry.

Having said all that, what we actually do with our scientific findings is also really important. We are not research machines. We are human beings. Good science is characterised by its ability to effect change and positive action.

Change

Many climate scientists will keep churning out papers that better chronicle the degradation of our environment and climate, without themselves doing anything different in their own lives. Choosing to stay in one's job and repeat standard phrases about the need for change indicate that, in spite of it all, it's fine to carry on as normal.

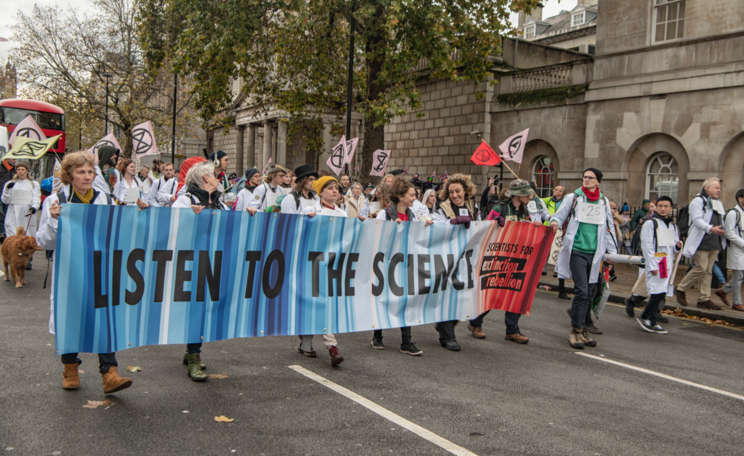

Fortunately more and more scientists are speaking out more forcefully. Let's not forget that this topic isn't about one paper or one professor.

For instance, Professor Aled Jones, of Anglia Ruskin University, and Australian National University emeritus Professor Will Steffen, have detailed the evidence for why “it’s time to talk about near-term collapse.”

Two hundred scientists have warned of the likelihood of “global systemic collapse” due to the way different climate and environmental stressors can interact and amplify each other. In a public letter to The Guardian, twelve climate scientists wrote: "it is time to acknowledge our collective failure to respond to climate change, identify its consequences and accept the massive personal, local, national and global adaptation that awaits us all.”

Can you imagine how it feels when someone reaches that conclusion? For me at times it has been difficult to find motivation to continue. It is the creativity and courage from people in the fields of Transition towns and Deep Adaptation that help me maintain my purpose.

Good science

I have had the enormous privilege of training many of the pioneers of Transition towns in many part of the world. They are an amazing and inspiring group of people.

From permaculture projects in Chile, to literally hundreds of community energy projects across the UK, to rural community resilience in thousands of communities worldwide we are revisioning and rebuilding our world town by town and community by community. This, for me, is important work for our time, and the learning that comes from these collective efforts will serve us and future generations.

Some scientists may be looking down at us from the windows of their libraries and labs, to tell us we must keep believing in reform and technology. Who are they trying to convince? Could it be one another and themselves?

Perhaps in time more of them will discover that it is ok to leave the safety of their old stories of professionalism. They may recognise their limitations, learn to be more transdisciplinary, and join a more critical conversation.

In my view, that would be good science.

This Author

Naresh Giangrande is co-founder of Transition Town Totnes, the first Transition Town, and of Transition Training.